For non-Muslim expats, Ramadan is a significant time of the year, but mostly in that we are aware of the change in working hours and the fasting requirements of those around us. Past this, many of us don’t truly feel part of Ramadan or understand its importance to a Muslim family.

In the hopes of bringing some small insight into what this holy month means to Muslims in Qatar, we asked three women in Doha to share their own family traditions and to explain how Ramadan affects them and their families.

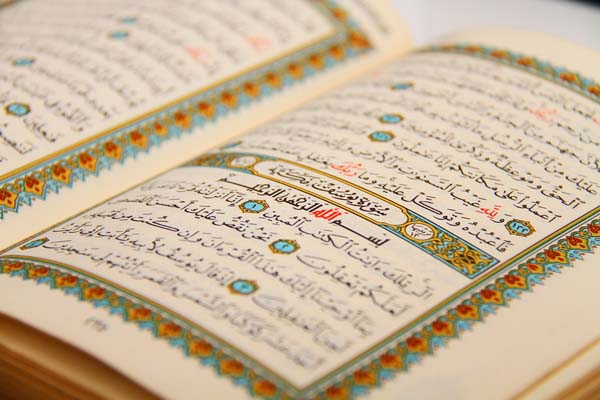

To start, Ramadan is much more than just not eating or drinking. One of the five pillars of Islam, it is a time to purify the soul, refocus attention to God and practice self-sacrifice. It is about refraining not just from food but bad thoughts, words and behaviour. It is also about bonding with one’s community and family.

A spiritual recharging

To Reem*, a Qatari woman who lives and works in Doha, Ramadan is a spiritual journey. It is also a chance for her family to come together and catch up with one another.

“It’s such a family affair and a moment of bonding for families as you’re in the kitchen together and at the dining table together. It’s exhausting, but very special and my favourite time of the year.”

For Hend Zainal, a Qatari working mother and wife, Ramadan provides an opportunity to step back and put things in perspective. For her, the holy month is a way to recharge spiritually. Outside of Ramadan, she finds herself so busy that this period becomes a good time to set priorities straight and reflect on the things that consume her every day life.

It is also a time for her five-year-old daughter to catch up and get to know the whole extended family within Qatar. On Thursdays and Fridays during Ramadan, Hend and her family get together at her eldest sister’s house— the crowd can get as large as 40-60 people, many of whom they may not see as frequently outside of Ramadan.

Fasting

Young children, pregnant women, the elderly or ill usually do not fast, but when Hend was only seven years old, a friendly competition with her brother gave her her first experience of fasting. “I wasn’t obliged to [fast] but I remember going through recess and my friends started to eat a burger in front of me and it was such torture. Needless to say I broke my fast that day.”

Reem was 14 when she first decided to fast. When her family questioned her readiness, she stubbornly stuck to her decision even though fasting was quite difficult. “I still remember this,” she said. “I actually thought I was dying to the point where I couldn’t speak.” At the height of her fasting struggle, her sister passed her a note (which Reem still has) asking if she wanted to give up. “I scribbled ‘No,’ only because I had an hour left.”

Amaney Neihoum is a Libyan expat who has lived in Qatar for several years with her husband and two children. She has experienced Ramadan in the U.K., Egypt, Libya and Qatar and has found that each country offers something different..

Amaney’s earliest memory of Ramadan is lunchtime in the school playground when she lived in the U.K. “Since it was my brother’s and my first Ramadan, my mum had packed in our backpack a Mars bar and a packet of crisps in case we needed to break fast to be like our friends.”

Being in the U.K. in winter, the sunset at about 4:30pm, which made it easier to keep to her fast. That packets of crisps and Mars bar stayed in her bag the whole of Ramadan until she finally indulged. “They were crushed but they were salt and vinegar crisps so they were delicious,” she laughs.

Breaking fast

As you can imagine, with having to fast all day long, food plays an important role in Ramadan. It also, as Reem says, brings people together.

Both Reem and Hend’s families end their fast with a modest meal or snack. Reem’s father always breaks his fast with a soup and salad and one protein dish. Her family makes a conscious effort to try and eat healthily and not over eat during Ramadan.

Hend’s family breaks their fast with dates, yoghurt, soup and carbs (typically pastries) before their evening prayer. For the main meal, they eat rice, salad and traditional Qatari food, such as threed, a dish of pieces of bread soaked in meat, beef or chicken stock.

The staple dish of Reem’s family during the holy month is harees, a soft porridge with veal

For Amaney’s family, a Libyan tomato-based soup with lamb, pasta and chickpeas is their traditional Ramadan dish. They also eat appetisers like bourek, a filo pastry stuffed with minced meat, spinach and cheese.

In addition to these main dishes, all three women described a variety of salads and side dishes. These smaller dishes are important because, as Amaney explains, “If you’ve been fasting all day, these side dishes are lighter and more manageable.”

But don’t forget about water. All three women stress the importance of drinking enough water each night before fasting. In fact, both Reem and Hind say they often drink anywhere from three to five litres of water to make sure they are well hydrated before their fast.

Charity

While their appetites might be modest after fasting all day, there is never a shortage of food. It is customary during Ramadan to gift food to neighbours or people in need. Sharing food isn’t just kind; it’s also a way to make up for days when a person is unable to fast.

As part of this sharing spirit, Reem’s family and neighbours often exchange food. Her aunt even hires an extra cook to prepare food for others. During Ramadan, people line up with their Tupperware containers for her food.

“There are many expat families and Qatari families who are struggling; and the good thing about Qatar is we all know each other so we keep everyone in mind and help,“ says Reem. “This happens in so many Qatari households, where you can come and be fed without anything being expected in return.”

The charity doesn’t stop with sharing food. During Ramadan, all Muslims are expected to donate a certain percentage of their earnings to charity or given directly to people in need.

For Hend, the charity and donations are the most important part of Ramadan, “The whole idea is to put yourself in the shoes of someone less fortunate.”

Garangao

Around half way through Ramadan is Garangao. According to Reem is it like “a Muslim Halloween party.” The origins of this cultural event are unclear. Some accounts credit it as a celebration for children who have memorized 15 chapters of the Qur’an, while others claim it is based on the celebration of the Prophet Mohammed’s grandson, Hassan. Whatever the origin, this children’s festival is unique to the Gulf more than anywhere else. Children dress in traditional Qatari clothes, sing traditional songs and carry a pouch to collect sweets and nuts from the neighbourhood. “The streets are filled with kids. There are tons of kids running around asking for sweets even though their bags are full,” Reem says.

Ramadan for non-Muslims

If you’re interested in Ramadan but not a Muslim, try out one of the hotel Iftars. However, be forewarned that they’re not a very authentic experience. Both Reem and Hind believe that the hotel Iftars are geared more towards expats and prefer to break fast at home with family. “[Fasting] is exhausting and all I want to do is go home and break fast, whilst if you’re out of the house you have to make more effort and have to be alert,” Reem says.

Hind agrees, “What you would see in a hotel Ramadan tent is very different to what you would see in a Qatari home. It’s more family orientated at home and more geared towards refraining from overdoing. In hotels they are obliged to put more and more of everything and there’s typically entertainment [which would be unusual in a Qatari home].”

If they are going to celebrate in a more public way, it’s during Suhoor, a gathering that takes place before fasting begins and can go on late into the night. For Reem, it’s a chance to invite friends and colleagues once she’s rested and has eaten, so she’s ready to enjoy the company of others. “If you get invited to Suhoor, you should make a dessert; bring chocolates or food but nothing else.”

Despite the inauthenticity of the hotel version of Ramadan, Amaney encourages non-Muslims to enjoy the hotel Iftars and different Ramadan cuisines around Doha. The smaller local restaurants, like those in Souq Waqif, put on more traditional foods than the big hotels. “Go and have a look and try it,” she says. “Go out with friends and really see what traditional food means.”

Otherwise, you could always try fasting for a day or two to get an idea of what Muslims go through during the day. One year when Amaney was young, her non-Muslim friends at school decided to fast with her. “Twice my friends tried to fast the whole day with me and then they would break the fast with me. They’re not Muslim and so it was really nice that they chose to participate in what I was doing and really tried.”

The peace and quiet many Muslims seek during this holy month makes Ramadan a pleasant time to be here in Qatar as the general atmosphere calms down and people slow down. It’s also clearly a time where, despite the personal and private family affairs, the individuals we talked to encourage us to be friendly, ask questions and not shy away. If you’re lucky enough to be invited to a Suhoor, be sure to come ready for a feast well past midnight and the warmth of many people under one roof—but don’t forget to bring a dessert in thanks!